Chapter III: Nanking

Chapter III

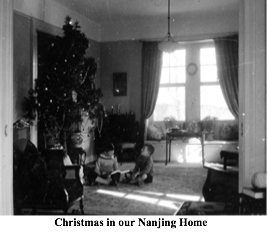

Nanking 1936 – 1937

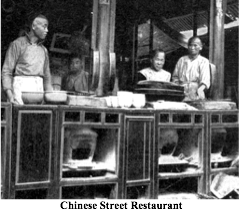

A Chinese City

As we walked the streets, there was no need to be afraid. There were fascinating shops all along the way, and we would often stop to buy a ‘baotze’, a round dumpling about the size of a baseball, with a little filling of sweet bean or savory meat in the center. The street-children hurled epithets at us wherever we went: ‘Yang guei-tze’ – foreign devil – was the kindest. They also told us to do things to our mothers that were not nice. But it was all done in good humor, without menace.

Throwing Stones

On one fine day the bus passed by our front gate, and for some perverse reason I threw a small rock that hit the side of the vehicle. To my surprise and rising terror, the bus stopped. The driver came out shouting obscenities, and banged on the front gate. I clambered down the ladder, ran into the house and hid under a bed, while the servants answered the gate. They subsequently came calling, ‘Bobby, Bobby”, but fortunately Bobby was not found.

It was 1937 and the Japanese had bombed Shanghai, had occupied Manchuria, and were threatening Nanjing. Although my father and two older brothers would stay in the Orient throughout the war, it was time for John and me with our mother to get out of China.

The War

What follows was written to fill out some very important family history, even though I was too young – then 10 years old – to be an active part of it. My father and two oldest brothers, George K (Kemp) and Albert, stayed in China throughout the war with Japan. Kemp worked for Texas Oil Company – Texaco – supplying petroleum products to the Chinese over the “Burma Road” after the eastern ports were cut off by the Japanese. It must have been terribly stressful with daily air raids on Rangoon (now Yangon), his base, by the Japanese to the point where he had ulcers so severe that emergency surgery was required. The doctor then sent him back home for total rest for the next several years.

Albert joined the OSS – Office of Stategic Services, now the CIA, took a crash Chinese language course at Yale University, and then spent several years behind enemy lines in China. He came home after the war a bitter, haggard alcoholic. He did ultimately recover to a happy, adventurous family life.

My father stayed in Nanjing in the winter of 1937 when the Japanese entered the city and unleashed a holocaust of unimaginable horror. He did all in his power to shelter innocent civilians and military who had put down their arms. The mayor of the city asked my dad to take over his position as he fled to western China to avoid certain assassination. Dad also was involved in organizing and operating the Safety Zone where non-combatants could be sheltered under an agreement with Jaapanese authorities.

The City of Nanjing now memorializes those events every 13th of December, the day the Japanese entered the city. They have built a huge and beautiful but powerful museum to honor the 300,000 innocents who were slaughtered. In 2016 I was invited to participate in those ceremonies, and upon my return I wrote a report. Here it is:

The Nanjing Massacre of 1937-38

In the bitter winter of 1937, as a prelude to World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army had invaded coastal cities in China and now moved on to Nanjing. They bombarded the ancient city wall to create an opening to allow troops to pour in. No words can describe the apocalyptic events that ensued. The Japanese military commanders told their troops that the city was theirs and that they could do whatever they wished with it.

The soldiers committed massacre upon the innocent citizens of Nanjing on a scale that was beyond imagining. The result was that some 300,000 noncombatants were murdered, the city was pillaged and burned, untold numbers of women were raped, and beheading and bayonetting contests were held among the soldiers.

Prior to the entry of the Japanese army negotiations had been held to establish a safety zone within the city in which the military promised not to disturb innocent people. The organizers of the safety zone comprised about 10 foreigners –– business people, missionaries, and medical doctors. My father, George A. Fitch, was asked to be the Director of the Safety Zone. As the members of the local government fled, the mayor asked my father to act in his stead. He gave the keys of the city offices to my dad along with a staff of two secretaries and a large supply of grain to feed the people during the attacks.

The call went out to the citizens of Nanjing, and some 250,000 came and were protected in a series of enclaves within the Safety Zone. From there they could watch their beloved city burning, their few worldly goods stolen, their homes destroyed and many thousands of cases of rape visited upon innocent girls and women. Often the boundaries of the safety zone were violated and people were dragged off to be murdered, raped and and horrendously treated in all kinds of inhuman ways. And my father had to watch our own home burned and looted.

One member of the safety zone committee was an Episcopal priest, John Maggie, who recorded movies of many of the atrocities surreptitiously. The films were subsequently sewn into the lining of my father’s heavy winter coat. He then boarded a Japanese troop train going to Shanghai, an act of incredible bravery, considering that he would have been shot on the spot if the films had been discovered. He was compelled to get the news of the atrocities out to the rest of the world. My

father subsequently lectured across the United States and testified in Washington about what had happened in Nanjing, and he warned of the impending threat to the entire world of Japanese imperial aggression. Business interests in the US largely ignored his warnings because of favorable trade with Japan. And so it took the attack on Pearl Harbor to convince the world, and for the United States to enter the war.

After the war the Western powers were preoccupied with reconstruction. The devastation of China was largely ignored. Adding insult to injury, Japan re-wrote history to deny that Nanjing ever happened. For decades the Chinese

attempted to warn the rest of the world about one of the most horrendous events in the history of mankind that occurred in Nanjing. The people of that city and their government have in recent years built a magnificent museum memorializing what had occurred in 1937. And they have declared December 13 to be their “Memorial Day”, with great ceremonies held at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum. Furthermore they have come to recognize that the documentation of the foreigners involved in the Safety Zone provides some of the most incontrovertible evidence of what occurred. So my task continues to be one of providing evidence from the Fitch family archives. Much of that now resides in the Yenjing Library of Chinese literature and history of Harvard University. In the 1980s I had taken the private papers and correspondence of my parents and organized them, collated them and gave them to Harvard.

So I was invited this time to participate in the memorial ceremonies on December 13. The hospitality of my Chinese hosts could not have been better. I presented to the Memorial Museum a copy of my father’s autobiography entitled “My Eighty Years in China”, and I helped the director of the museum with certain documents relating to my family.

Crowd of Thousands at National Ceremonies

The previous day I, along with a few other descendants of the Safety Zone Committee, was awarded the Gold Medal of the Purple Grass and I was asked to give a brief speech about my father. The main concern I had in that speech was the question of how could anyone stay in that holocaust and work towards helping the helpless when they could so easily have run. My father was a very religious man, a follower of Jesus, who when he was murdered on the cross said, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” So there was the lesson of forgiveness for the unforgivable. Jesus also told the story of the good Samaritan who found a member of an enemy tribe beaten and left for dead on the side of the road. The Samaritan picked up the man and took care of him until he was well again. Clearly my father was deeply influenced by these words, and lived by them. But there was more. He was born in China and came to love Chinese people as his own. How could he abandon them in their time of deepest need?

The museum of the Nanking massacre is a huge and magnificent edifice. Many of the 300,000 who died in that holocaust are buried within the grounds of the museum. The exhibits in the buildings document the horrors of that terrible winter. It stands as a great warning to the rest of the world that we must never forget what happened there, and we must strive to ensure that it never happens again. Working towards world peace seems like a Sisyphean task, but we have to keep at it until it is achieved.

♣