Chapter II: Shanghai

It’s so simple to be wise. Just think of something stupid to say, and then don’t say it.

– Sam Levenson

Chapter II

Shanghai 1928 - 1936

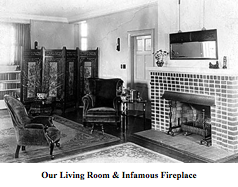

A Well-Regulated Family Life

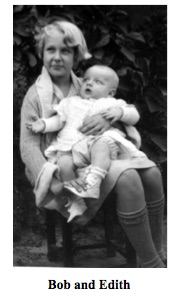

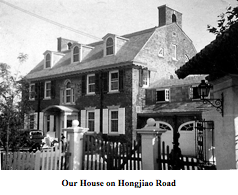

We later moved to a beautiful suburban house in Shanghai with a lovely garden in back and with lots of servants. Years later I once asked my mother how, as a devout Christian, she could justify having Chinese servants. Wasn’t it against her principles to have others of God’s children subservient to us? She replied that we were providing them with decent employment in an open relationship, i.e. that they could quit if they were unhappy with their situation. Oh. At the time that seemed to make sense. Later I realized that there was still a vast gulf between their lives and ours. But of course I came also to see a vast gulf within Chinese society; the rich had fabulous homes and gardens, deluxe cuisine, servants etc. An extreme example is the Humble Administrator’s Garden in Suzhou, covering almost 13 acres with many lakes and ponds, and buildings in traditional architecture.

Meals were times when the family was together, and therefore times for rules, regulations and discipline. Being sent away from the table occurred fairly regularly for minor infractions. We had Chinese food, which we loved, once a week. Every Sunday breakfast comprised either waffles or pancakes, with a limit on the number each person could have. The first waffle or pancake could not have anything sweet on it. It’s interesting to note that alreaady in those days that it was well known that sugar was bad for you. Of course, in that Protestant ethic, anything desirable was probably immoral. We not only counted our own waffles, but also those of our siblings to be sure they weren’t cheating by getting an extra, illicit one.

We had adult guests for dinner after church on Sundays. These were formal occasions, with conversation usually on political or social topics. Many of China’s movers and shakers broke bread at our table, and certainly enlivened our discussions. Teatime was always at 4:00 when John and I usually had a bottle of sarsaparilla, separately from the others.

A minor conflagration

Table manners were important: I was importuned at every meal to remove my elbows from the table. One ate soup by tilting the dish away from oneself, dipping the soup spoon (always the appropriate silverware) and sipping from the edge of the spoon, never putting spoon in mouth. I never understood such silliness. The only reason I can see for such rules is that they help to establish one’s position on the social ladder. Who would ever condescend to dine with someone who tilted his soup dish towards himself and stuck the spoon in his mouth?! But I did learn, over time, that the most important basis for all good manners should be simply a genuine concern for the other person.

Play time

In my father’s study there was a large Chinese desk with several drawers in which he kept interesting things. With too much idle time on my hands, and with parents often out of the house, I had discovered his cache of cigars and cigarillos (a hybrid of cigar/cigarette) in one of the desk drawers. It didn’t take much coaxing from my evil older brother to try smoking one of them, and thereafter to do it often when Dad was away, which was most of the time. In later years I would say that I quit smoking when I was ten, and didn’t take it up again until I was in college [see the chapter on Pasadena]. With no television and no chores to do, brother John and I had to create much of our entertainment, which meant inventing games and situations largely out of our fantasies. The space behind a couch became a magnificent castle, or we took turns claiming that we were the world’s most famous movie actor, or aviator, or person of wealth in a game we called ‘famousies’. It was a rich life of the imagination.

Thrift

Our parents taught us to be frugal and thrifty. One time while I was taking a bath, my father came into the bathroom and was shocked at how much water I had in the tub, maybe a third full. At the next occasion he was there in the tub with me to demonstrate how one could take a perfectly good bath in exactly two inches of water. Greeting cards could be saved and recycled. We were told to sign our Valentine’s or Christmas card in pencil, so that the signatures could be erased and the cards reused on later occasions. Of course string, scrap paper, rubber bands, and paper clips were all saved. To this day I save all of these things, even pausing before I throw out a small piece of notepaper if it still has some blank area on it. In our present society I am constantly aghast at the amount of waste we generate every day. The highest hill on the plains for miles around Racine, Wisconsin where we once lived, is the waste dump. ‘Mount Trashmore’ I used to call it.

Christian tradition permeated family life, and often for what seems to me were superficial reasons. We certainly observed the Sabbath and kept it holy: no comics in the Sunday newspaper could be read until Monday; no card playing; no movies (desirable, ergo immoral again!). On all days there were no alcoholic beverages. My parents were in China not to save souls; that they left to the missionaries. They were there to do good and to show the heathen how wonderful the word of Christ was.

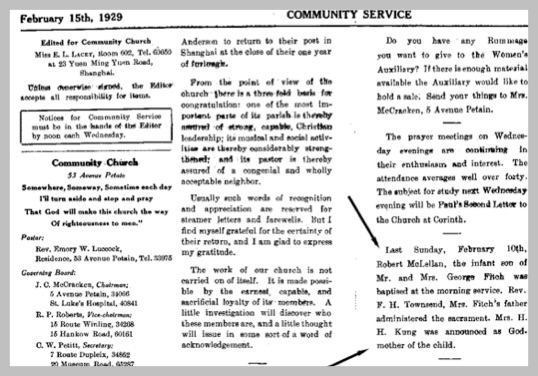

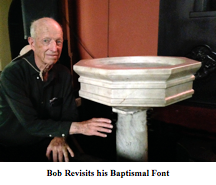

I was baptized in the Community Church located almost next door to our home. The occasion was published in the church bulletin (below), noting that “Mrs. H.H. Kung was announced as Godmother of the child.” She was Ai Ling Soong, one of the three famous Soong sisters, and married to K’ung Hsiang Hsi, the finance minister of China. Not surprisingly she was wealthy, but she also had a heart of gold. I was to be the beneficiary of her love and generosity over the years.

Her husband, “H.H. K’ung”, held several top positions in the government, and was probably the person most responsible for bringing China into the modern world after the revolution of 1911. Ai Ling’s sisters didn’t do too badly either: Ching Ling married Sun Yat Sen, the founder of the revolution and modern China, and Mei Ling married Chiang Kai Shek, the President of China at the time. Their brother T.V. Soong was a distinguished diplomat responsible for many negotiations among China, the United States and the Soviet Union.

My father had the good sense to recognize the innate qualities in many of his non-Christian friends and colleagues, and treated them with respect even though he was thoroughly convinced that Christianity was the best religion. Father was a towering presence in our family, and I regarded him as the quintessential Moral Man. He was my model to which I aspired, though failing often. It wasn’t until later in life that I acquired the maturity to realize that he was, after all, of this earth, but yet of high moral comportment.

It’s interesting to note that most of my cousins, the children of my father’s four siblings, were deeply religious. Some entered the ministry, others were involved in religious ecumenism, and others went into doing good, as in nursing. On the other hand all of Dad’s children were not involved in religious activities. I think most of us ended up as Christian agnostics; that is, we believed in many of the humanistic teachings of Jesus, but have had a hard time believing in an Almighty God, Creator of the Universe, virgin birth, miracles, etc. To some extent in my mind, this is a tribute to my father’s objectivity and open-mindedness. He came to visit me in Ann Arbor when I was completing my Ph.D. work in chemistry. He said how proud he was of me, and I’m sure he was. But I wonder if there wasn’t some yearning that at least one of his children, I being the last, would have gone into some sort of eleemosynary work.

Raising children

Thus my generation were the heirs to a family tradition steeped in religious life along with high expectations for the children. This led to feelings of inadequacy and social insecurity for me, and I believe, to bouts of alcoholism for two brothers and to chain smoking for another. But paternal high standards and discipline and maternal love ultimately gave me strengths that were invaluable throughout my adult life. When it came time for me to be a father, I tried to take from my parents what I thought was good practice in raising children, and to discard what was unnecessary, unimportant, or even harmful. More about that anon.