Chapter VIII: Dartmouth College

It is unwise to be too sure of one's own wisdom. It is healthy to be

reminded that the strongest might weaken and the wisest might err.

- Mahatma Gandhi

1945 – 1949

Dartmouth Days

Mom and Dad packed the station wagon with a carload of my gear, and we drove from New York City all the way to Hanover, New Hampshire. They stayed overnight so that they could help me get established in the dorm and have a nice dinner together in the Hanover Inn before going back home. Well, that’s the typical American family picture as painted by Norman Rockwell, but not my reality. I took a suitcase on the train alone. Dartmouth College at that time was an all-men’s institution (it became co-ed more recently).

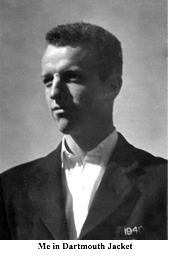

Upon entering Dartmouth I knew that chemistry was to be my major. By taking the freshman qualifying exam I was excused from the first semester of that course, and subsequently managed to earn an A for the second semester. This was 1945, the beginning of the atomic era. Our professor of chemistry gave a lecture on how the atomic bomb worked that fascinated me. I wrote a ‘theme’ on it for my English class, which that professor said was the best in the class for the week. I seemed to be on a roll! But there was a strong sub-culture on campus that drew me into its undertow, a jock-machismo-drinking emphasis that played on my insecurity. I wanted to be liked. My classmates were mostly from wealthy families who lived in very upscale suburbs with excellent school systems. They were mostly from business families, with an inordinate number in the insurance sector. Many of the parents were Dartmouth alumni; their sons thus had preferential treatment for admissions; not a few of them were playboys. I suppose it was more than accidental that the movie “Animal House” was based here. I wanted to be a playboy, too, but wasn’t very successful at it since I retained intellectual interests, especially in chemistry, but my grades were slipping.

In high school I had hated history – dates, battles, presidential and royal lineages – all that was deadly boring. To satisfy a distribution requirement in college, I took a European History course. It changed my entire outlook. There were still dates and battles, but much more: the development of culture: music, language, dress, science and technology. I loved it! Mathematics in my early terms at Dartmouth was interesting and engaging, but integral calculus just about did me in. The professor had no imagination, made no attempt to make it interesting, never showed us any practical applications, and lectured in a monotone. This had a terribly negative impact later on my progress in graduate school, especially in the study of thermodynamics and physics. The sophomore course in chemistry covered qualitative analysis of the elements, a snap for me after the tutoring I’d had in Wooster.

Later there was a course in the qualitative analysis of organic chemicals that was also thoroughly enjoyed. In the first laboratory session the professor handed each of us an unknown compound that we were to identify. I took a sniff of mine; hm-m-m, it smelled like an alcohol, but too ‘heavy’ to be methanol or ethanol. I went to the shelf, pulled out a bottle of iso-propanol (commonly sold as ‘rubbing alcohol’). Bingo! That was it. So, while the professor was still handing out unknowns to the class, I came up to him and said, “This is iso-propanol.” Without the slightest hesitation he retorted, “Prove it.” My effort to avoid hard work failed. But after doing all the laborious making of derivatives and taking melting points, etc., it was indeed iso-propanol. And therein was a lesson about the nature of science: superficial ‘sniffs’ will never satisfy the need for thorough proof when investigating the mysteries of the physical world.

Chemistry majors are at a disadvantage with regard to extra-curricular activities because of the need to attend labs almost every afternoon. I did manage to be in the Dartmouth Glee Club for two years. Of course we gave concerts on campus, but we also toured to small towns in New England. Once we sang at Dartmouth Night in Symphony Hall in Boston. I was thrilled to be in such a hallowed place, but was totally unprepared for the ovation that we received after singing the Alma Mater and football rally songs to such a partisan crowd. The roar of shouting and applause in that venerable and staid venue just about floored me! We had a little routine that was always a crowd pleaser: Before this particular number we turned our backs to the audience, took off our jackets, dropped our trousers, and then turned around. We had on short pants, white shirts and wide, silk cravats to look just like a group of nice choirboys. Then we sang in falsetto our modification of a famous Christmas song about the birth of Christ:

Lo, how a rose ere blooming

From tender stem hath sprung.

We sing this song in English

‘Cause we know no foreign tongue.....

Well, it brought the house down! I was able to stay with the Glee Club for two years, but then it was necessary to give it up.

I had also joined the ski team, and trained primarily for cross-country, which was my forte. To get in shape, I ran regularly for miles through the golf course and along the Connecticut River. It was all soft turf under foot, beautiful countryside, and I truly enjoyed it. But when it came time for ski competitions, somehow I always went missing. Out of town tournaments meant getting to the bus before dawn, an extremely difficult task for someone with a saturnine diurnal rhythm. I just couldn’t drag myself from bed, alas! Being on the team had to come to an end anyway, as labs took up more of my afternoons.

My father, for a good part of his life, had put some of his earnings into an education trust account for his children through an insurance company. I don’t know what the others received, but as the last of six, I got the munificent sum of $25 every month, which in an Ivy League college didn’t go very far. It did help, although I had to earn more if I was to survive. Initially this was with the College dining services, and later doing all kinds of odd jobs around town, e.g. waiting on tables in local restaurants and the nurses’ house (that was fun!), working for a laundry, etc. In my junior year the chemistry department offered me a teaching assistantship (TA) that meant I had to prepare the chemicals in the stockroom and supervise freshman labs. It was an amusing shock when one of the students would come up to me to ask a question, and address me as ‘Sir’. What would be the term used today, I wonder?

All seniors had to take Comprehensive Exams prior to graduation; mine would of course be in chemistry. One afternoon while studying in the Chemistry Department library, Prof. Wolfenden who was teaching the physical chemistry course to us at the time, was chatting with me there in the library when he said, “You know, Fitch, I think if you really studied hard you could get a C in the Physical Chem Comprehensive Exam.” I was thunderstruck. A C! It was an insult, but it had its (intended?) effect. Every distraction was swept aside as I devoted all my energies to that exam over the next few months. Several days after it was over, I was bicycling through the village of Hanover on a lovely fall day when I passed the good professor raking leaves on his lawn. I stopped to chat; he looked at me as if he were seeing a strange apparition, and said with wonderment in his voice, “You wrote the best exam in the class!” I believe I was as surprised as he – but greatly pleased.

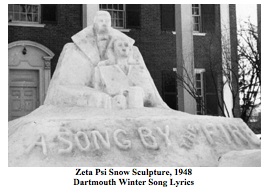

Girls were not a big item in my life at Dartmouth, believe it or not. After all, it was a men’s college in a small town in the north woods of New England, land of the Puritans. The medical school’s Mary Hitchcock Hospital served as a regional medical center with a fairly sizable contingent of nurses. Student nurses lived in a home provided for them, and at one point I got a job waiting on table in their dining room, as mentioned earlier. This was a good resource of sweet and attractive young women. Nothing serious ever developed from any of those relationships, though. They just weren’t intellectually stimulating, which for me is the ultimate aphrodisiac. I did have one big crush for a while. A New York friend introduced me to her pal, Shirley from Louisiana, who had come to the Big Apple to find her fortune. We hit it off immediately, spending a lot of time together in the city. Although we had many happy hours together, I got the impression that I was to keep my hands to myself. She came up to Winter Carnival one year, but seemed subdued and not much impressed with Ivy League culture. Soon thereafter she returned to Louisiana, and even though we corresponded for a while, it was eventually over.

It was on to great adventures on the high seas for me, shipping out from La Jolla, California as a Marine Chemical Technician with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

♣